|

|

|||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||

|

Power Your Equipment Safely by Mark Persons |

Radio

World Article February 13, 2019 |

|

You can never have too much power protection |

|

|

Yes, ground fault circuit interrupters are a nuisance at times, but they are there to keep you safe from 120 VAC power. These devices are required wherever there is water near electrical circuits, such as in kitchens, bathrooms, garages and on outside outlets. A man recently was killed while standing in water, holding an electric drill at a lake dock. There was a short between the metal case of the drill and its power cord. He was electrocuted instantly. That could have been avoided if the drill was plugged into a GFCI-protected outlet. A small amount of current to ground would have shut off the GFCI breaker and saved the man’s life. The same applies on my service bench. I get an occasional GFCI trip, but it is a minor inconvenience when the result could have been injury or death. It also tells me when I have a piece of equipment that has leakage to ground and should be worked on before it goes into service. A power cord’s third wire is a safety ground that goes to the equipment chassis. Yes, there are devices today that have two-wire power cords. Look for a UL sticker, showing the equipment has been tested by United Laboratories and is deemed safe to use. Check equipment at your stations. If you find a two-wire powered device without a sticker, replace the equipment or consider modifying it by replacing the power cord with one that has three conductors. That third wire, the ground, needs to be connected reliably to the equipment case. Years ago there were no ground wires. It was normal on occasion to get a tingle from a radio receiver with leakage to its chassis. You are in greater danger today of being shocked, or even electrocuted, from one of those older devices. A power transformer can develop a short from a winding to its core. That could put a full 120 VAC on the metal case. Ouch! |

|

|

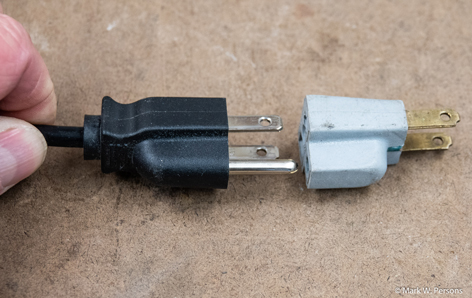

CHEATING

CIRCUIT

PROTECTION |

| Fig. 1: Don’t use a cheater adapter, like the one shown here. | |

|

|

|

|

|

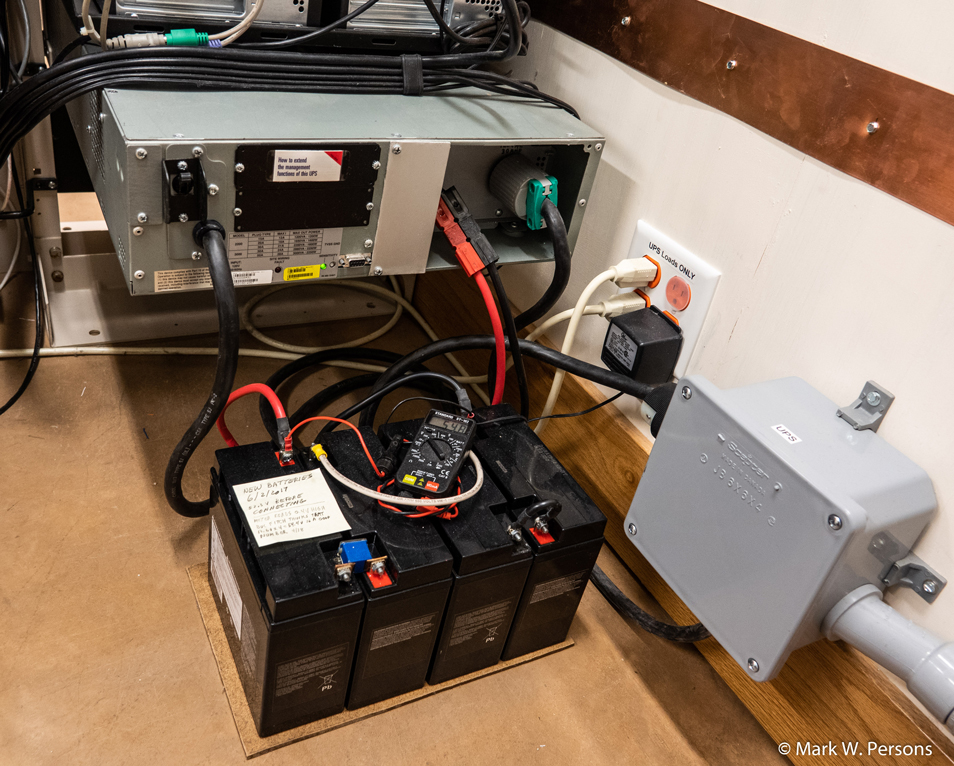

| Fig. 2: UPS batteries kept outside the UPS. | |

|

Fig. 2 shows the one at my place. The photo shows only see the back of this rack-mounted 3000 watt APC brand UPS. On the batteries are a permanently attached inexpensive voltmeter and documentation showing what date the batteries were installed, along with the normal voltage. As the only UPS in the facility, it runs seven computers, a security system, smoke alarms, the internet connection and a phone system. The UPS only needs to run for the 10 seconds required for the automatic backup power generator to come online, plus 10 seconds or so for the UPS to deem the power safe before switching back during a power outage. It is a good and seamless system. The grey PVC box, to the right, handles 120 VAC going to and from the UPS. Wiring is arranged with plugs and jacks so the UPS can be easily bypassed if it fails. |

|

|

UPS POWER

DISTRIBUTION |

|

|

|

| Fig. 3: A surge arrester in a circuit breaker panel. | |

|

Added to it, and all other load centers in the facility, are Square D QO2175SB Surgebreakers (a trademark name of Schneider Electric) that plug in like standard circuit breakers. This product is the size of a two-pole circuit breaker, but without a breaker handle. A green light indicates all is well. Its job is to shave voltage spikes from lightning strikes and power surges. The Surgebreaker is even, as I understand it, capable of drawing enough current to trip the main breaker in the box and thus protect the connected equipment. Likely other manufacturers have similar products. Every circuit breaker panel should have one. You can never have too much power protection!

CLEAR MARKING |

|

|

You should use electrical outlet safety caps to keep people from inserting a power plug where it shouldn’t be. Covers often come in 12 packs for about $2 (Leviton 12777 or equivalent) at hardware and department stores. You can use any extra covers to help keep electrical outlets safe from kids at your home. |

| Fig. 4: Safety covers are used to protect power outlets. | |

|

LIGHT BULBS If the lamp is a #47, it is rated at 6.3 volts and draws 0.15 amperes of current. To find its resistance, divide 6.3 volts by 0.15 amperes. The answer is 42 ohms. Adding a resistor of one-tenth that value in series will result in about a 10 percent reduction in voltage at the lamp. A 4.7 ohm resistor is the nearest standard value and is close enough. Now the lamp runs at 5.67 volts and is almost as bright as it was at 6.3 volts. The other important resistor rating is its power dissipation capability. Ohm’s Law tells us that just under 0.1 watt will be lost to heat in the resistor. Use at least a 1/2 watt resistor because it will be dissipating power/generating heat whenever the light is on. More resistor wattage capability is better in this case. There are replacement LED lamps that are direct drop-in replacements today. On the other side of the coin, incandescent lamps will run the same on AC or DC power. LEDs want DC at about 2 volts. Use a series resistor to keep current within LED specifications. I typically like to see LED indicators run with 10 m.a. of current. You can use them on AC if you don’t exceed their maximum allowed reverse voltage specification, which could be as low as 5 volts. A #47 lamp might cost less than $1 while its LED drop-in replacement, with built-in resistor or other electronics, could be $7.

DO IT SAFELY |

|

|

Mark Persons, ham W0MH, is an SBE Certified Professional Broadcast

Engineer and SBE Engineer of the Year in 2018. He is now retired after

more than 40 years in business. His website is www.mwpersons.com. |

|

|

This is a reprint of the article which appeared in the online

version of Radio World at:

https://www.radioworld.com/tech-and-gear/tech-tips/power-your-equipment-safely Comment on this or any article. Write to radioworld@nbmedia.com. |

|

|

Questions? Email Mark Persons: teki@mwpersons.com |

|

.